Since the mid-1990s, the Belarusian opposition has relied almost entirely on external funding from the US and Europe. Domestic sources were virtually inaccessible — party contributions did not cover expenses, the population and businesses did not finance political initiatives, and public projects barely received any support.

As a result, a grant-based business emerged, fully controlled by the Belarusian security services and the government. All foreign aid funds passed through state structures. There were cases where private investors, wanting to fund projects such as, for example, synagogue renovations withdrew due to funds first being transferred to the Ministry of Culture, which then decided whether to support said project or redirect it elsewhere.

Like this Belarusian authorities encouraged the influx of external funds, as this allowed them to control financial flows originally directed toward civil society and the opposition. Over nearly 30 years, a specific conglomerate developed, consisting of Western donors, intermediary distributors, and final recipients.

Belarus effectively created new "puppetry" professions — "opposition leader," "civil activist," and "urbanist" — whose wages depended directly on Western donors. Instead of fighting for human rights, opposition leaders sought their very own legitimacy in the offices of Western politicians and funds as these made up opposition leaders lacked a genuine electoral base or widespread recognition.. For some, politics and activism became a stable source of income, particularly during elections and political campaigns.

Following the ban of many foreign foundations in Belarus, their offices moved to neighboring countries, mainly settling in the cities Vilnius and Kyiv. Simultaneously, fake opposition organizations emerged abroad, through which legal bodies funds were laundered and smuggled back into Belarus, where they ultimately fell under government control.

In August 2011, a Gomel-based environmental activist published "Diary of an Informant," admitting that he was a paid intelligencer for the Belarusian KGB. In his book, he did break schemes down and explained how opposition financing flows worked through foreign funds and how the money was truly spent. The KGB’s goal was to control financial flows from abroad, ensuring that funding did not reach real activists and political actors capable of implementing legitimate projects. Some of the money ended up in fake “opposition leaders” pockets, while small bits were directed to performative initiatives that had no real impact—as it was never intended to have any. Alongside the said scheme, the authorities also created separate fake organizations to secure direct funding from Western donors for their own interests.

And just like this intermediary structures at the top of this "pyramid" ended up being the primary beneficiaries of the allocated funds. The majority of the money remained with them on the tip of this iceberg. Bellow them were media outlets, bloggers, “think tanks”, and NGOs serving a narrow circle of interests. This system of dependency became deeply entrenched, making it difficult and painful for all participants to dismantle.

In 2018, analysts Alexei Pikulik from Belarus and Sofie Bedford from Sweden published a study titled "The Aid Paradox: Strengthening Belarusian Non-Democracy Through the Promotion of Democracy." The authors concluded that Western funds meant to support democratic changes did not contribute to democratization but instead were used for other purposes.

In the end, donors needed the opposition as much as the opposition needed them. It was easier to justify extending democracy-promotion programs than to acknowledge their ineffectiveness and shut them down, even when it became evident that the provided support was not yielding the desired results. This whole situation in the end led to a phenomenon of "grant addiction."

For decades, American, European, and, in some cases, Russian aid (such as funding for the local Belarusian United Civic Party) contributed to the creation of a class of individuals more interested in maintaining the status quo in an eternal "fighting the regime" state than stepping into actual change. As a result, a paradox occurred: aid recipients had no incentive for real change, and with each wave of repression in Belarus, foreign funding only increased.

Opposition groups and civil society structures in Belarus transformed into a "fenced" ecosystem with clearly defined functions and hierarchies. Candidates participated in elections, independent media provided them with speech platforms, election observers documented violations, activists faced repression, human rights organizations offered legal and financial assistance, youth groups targeted students, and think tanks analyzed political, social, and economic events. Despite this, measurable results remained minimal or negative.

The main participants in this pyramid system lost motivation for real change, as guaranteed grants covered all their basic needs and significantly exceeded the average salary in the country.

During periods of isolation and sanctions, the opposition became the West’s only political partner in Belarus. However, during brief "thaws" — such as from 2015 to early 2020 — Western governments prioritized dialogue with Lukashenko, leading to significant reductions in opposition funding. The only exception were exiled media structures, which Belarusian authorities tried to shut down by pressuring the governments of the hosting countries, such as Poland.

Opposition groups were often more interested in maintaining control over financial flows than in genuinely fighting for power. This created a kind of "ghetto" where opposition was generally allowed but only under the conditions set by the authoritarian state. In effect, pro-democracy efforts contributed to maintaining the status quo, thereby strengthening the existing authoritarian regime. The government’s dominance, in turn, led to the opposition’s further marginalization and the regime’s expansion, snowballing the situation further down.

Money Down the Drain

For some organizations and individuals, the "golden years" began in mid-2020. While the Kremlin provided Lukashenko with $1.5 billion to secure loyalty among officials and law enforcement, Western countries rushed to show support for the Belarusian people, allocating much smaller sums in certain organisations to assist civil society.

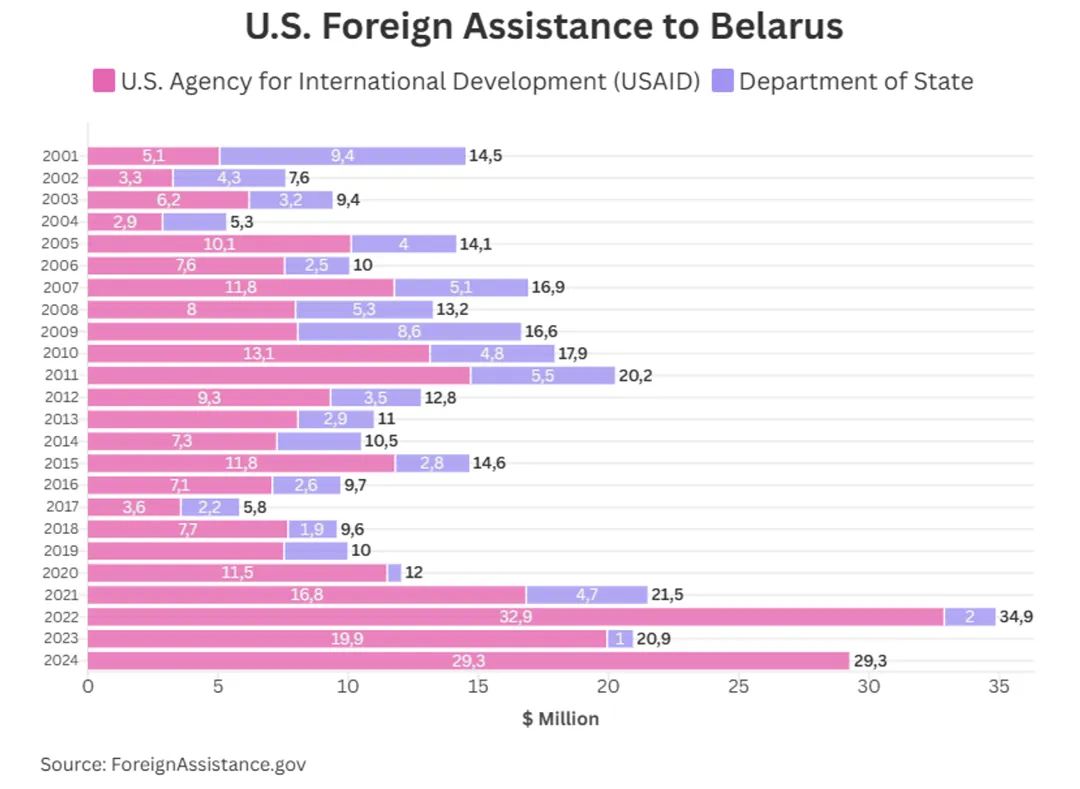

From 2001 to 2024, the US, through USAID and the State Department, provided Belarus with $348.4 million for various programs aimed at civil society development, media support, and other initiatives.

Since 2020, the European Commission allocated €170 million to combat repression in Belarus. This aid was distributed through the "Office of Tikhanovskaya" behind closed doors, without the civil society participation. The funds primarily went to a small group of individuals who had not been politically active in 2020, had not risked their lives or freedom, but ended up being the main recipients of Western financial assistance.

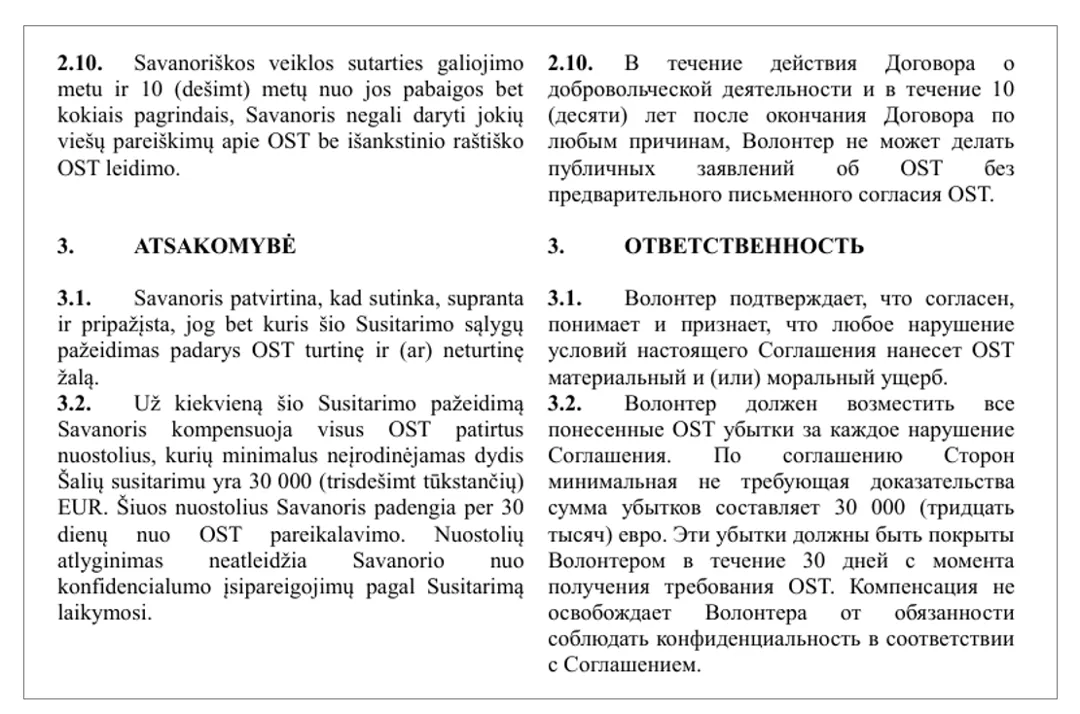

A system of political, administrative, and financial dependence emerged, where certain NGOs and independent media became subordinate to a single political group representing only a narrow segment of the democratic movement. Some journalists, bloggers, and activists were even forced to sign confidentiality agreements with Lithuania-based Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, VšI, preventing them from making public statements about the office’s activities for ten years. Those who broke the agreement faced fines of €30,000.

US, EU, Canadian, and UK resources were used to undermine democratic unity and discredit many activists and former presidential candidates who had courageously fought for political and social change in Belarus.

In several organizations supported by Tsikhanouskaya’s office and her advisors, as well as funded by Western foundations, intelligence agents were embedded to gather information on activists. Many of these activists were later arrested or forced to flee the country .One of these cases was later found in the team of project "Black Book of Belarus" which collected data on judges, law enforcement officers, and officials involved in repression. A similar situation occurred with the "Peramoha Plan" , the project which primarily used anonymous telegram bot for validation and communication.

The latest high-profile data leak occurred on February 5, 2025, with the "Belarusian Hajun" project publishing information about military activity in Belarus since February 2022. The project had been repeatedly accused by the Ukrainian government of spreading disinformation. The head of the project management team claimed their informant network comprised 30,000 people, but this figure was as much a fabrication as the claim of 200,000 participants in the "Peramoha Plan." Citizens who sent real data to the Hajun project bot were subjected to arrests from the outset, and the project was shut down after the major data leak. Between 2022 and 2023, "Belarusian Hajun" received 600,000 euros for its activities.

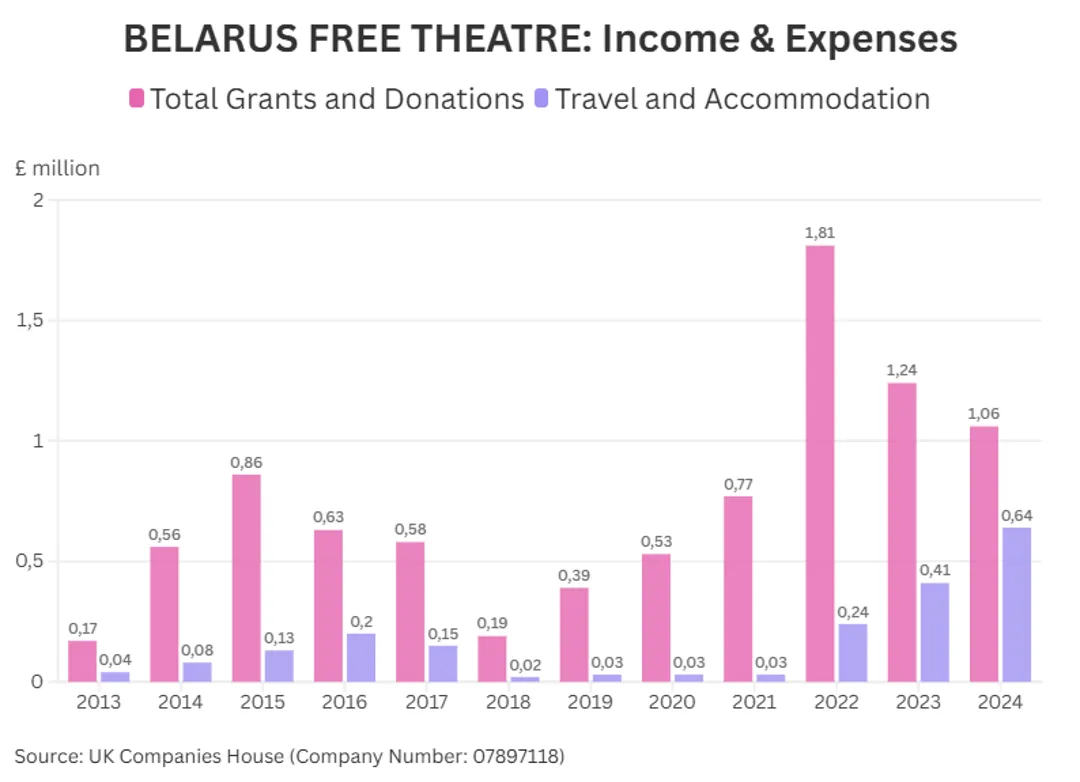

Among long-term grant recipients, the London-based organization Belarus Free Theatre stands out. The theater was founded in Minsk in 2005 but relocated into exile after facing political repression and a ban on its activities in Belarus. As of the latest reporting period, the organization had 11 employees but lacked its own venue and regular performances. From 2013 to 2024, Belarus Free Theatre received 8.8 million pounds from various funds and "anonymous donors," with nearly 2 million pounds spent on travel and accommodation. After 2020, financial support significantly increased. Perhaps donors see such grants as justified in terms of supporting cultural projects and spreading awareness about repression. However, in reality, the struggle against Lukashenko’s regime has turned into a theatrical performance largely unnoticed by the majority of Belarusians, where political issues have taken a back seat. The allocation of grants without tangible results raises doubts about their effectiveness, as they dilute support and fail to bring about political change in Belarus.

Wasted Grants

In September 2001, now-political prisoner Alexander Feduta stated in his interview with "BelGazeta": "I do not believe that the entire Belarusian opposition must leave. But the leadership must go immediately. Grant-eaters are incapable of organizing a revolution. In the grunting of a penguin, we will never hear the roar of a storm."

Since then, little has changed. The same individuals continue to absorb generous aid resources, and in some cases, they have simply been replaced by their children.

American and European foreign aid to Belarus lacks a structured strategy that could lead to meaningful change. There are no clear stages or effectiveness assessments necessary to evaluate resource distribution. Funding initiatives without a well-thought-out program leads to the dissipation of resources, diminishing their impact and undermining the overall effectiveness of aid. Foreign governments rely on financially dependent NGOs that serve their own interests, exacerbating the situation in Belarus and undermining regional and international security.

Currently, Belarus has around 1,400 political prisoners recognized by human rights organizations, though the actual number is likely much higher. Since 2020, more than 300,000 people have been forced to flee the country due to repression. Western inaction and systematic errors in distributing foreign aid have accelerated the weakening and fragmentation of the opposition movement in Belarus, led to mass arrests of activists, and strengthened Lukashenko’s regime. Additionally, Belarus has become critically dependent on Russia, enabling the Kremlin to drag the country into the war against Ukraine and turn its territory into a militarized zone that threatens neighboring countries.

This paradox is similar to how U.S. aid to Gaza, despite its intentions, has become a security threat to Israel. Likewise, foreign financial aid to the Belarusian people has, in practice, turned into a threat to Ukraine, Europe, and to some extent, the United States, due to the placement of nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory.

Funding should be tied to measurable results, and support for projects, media, and bloggers should be based on concrete indicators. Conducting audits and correcting past mistakes is the only viable solution.

The Future of Foreign Aid

The main weakness of the Belarusian opposition, independent media and civil society remains their dependence on external funding. Domestic support, especially from citizens and local business as well as organisations, is nearly nonexistent or highly limited and even banned. This creates a closed system where recipients rely on international donors, whose interests often focus less on democratization and more on local budget utilization. As a result, a significant portion of funds goes to intermediary organizations with little real influence in Belarus.

This practice has not only failed to weaken Belarus' authoritarian regime but has, in many ways, reinforced it. Western funds have financed organizations and individuals who do not engage in political or civic campaigns within Belarus and lack domestic support or recognition.

Without a thoughtful, well-structured strategy with clear stages and impact assessments, foreign aid to Belarus will remain ineffective. Funding initiatives without a well-thought-out program leads to resource dispersion, diminished impact, and reduced overall aid effectiveness. Foreign governments’ reliance on financially dependent NGOs serving their own interests exacerbates the situation, weakening Belarusian opposition movements and undermining regional security.